A Practical Guide to Scanning and Transmission Electron Microscopy Simulations

Physical Concepts

The properties of atoms, molecules and solids are fundamentally determined by quantum mechanics. In this modern theory of physics, some classical concepts such as the electrostatic potential and the propagation of waves are carried over essentially unchanged, whereas many familiar intuitions fail on the level of the very small. In particular, quantum objects including electrons exhibit both wave and particle properties depending on how they are observed — in the context of electron scattering, matter-wave interference is of central importance. Mathematically, both free propagating electrons and those bound into atoms are described mathematically as complex waves, via so-called electron wavefunctions.

Electron Wavefunctions¶

An electron wavefunction, typically denoted by ψ, is a mathematical description of the quantum state of an isolated quantum system. The wavefunctions are complex-valued, and thus not directly observable, but their squared amplitudes can be interpreted as probabilities to find the electrons in particular states that do correspond to physically observable properties of the system. Wavefunctions naturally live in a many-dimensional mathematical space called the Hilbert space. By choosing a basis of representation, they can be represented in real space, typically using either Cartesian (convenient for planewave propagation) or spherical coordinates (convenient for scattering).

Two kinds of wavefunctions are commonly encountered in the context of electron scattering: freely propagating plane and spherical waves, and wavefunctions of electrons bound by (a collection of) atoms. Plane-waves can be mathematically denoted as

where is the three-dimensional position vector, is the time, with magnitude is the three-dimensional wavevector for wavelength λ, and ω is the angular frequency of the wave. is a volume factor that ensure that integral of the wavefunction over all of space is equal to unity.

Spherical waves can be described similarly,

where now denotes the location of a scattering center, and the denominator ensures the correct decay of the amplitude as a function of inverse distance.

To describe the propagation of these waves in free space, the imaginary term in the exponential describes periodic variation. Thus for any fixed sum of the spatial and temporal terms in the exponent, the wavefunction has the same value; these represent the planes (or shells) of constant amplitude. To calculate the wave in an arbitrary position, we can simply substitute the new spatial location and time arguments to calculate the resulting amplitude.

Bound Systems: The Schrödinger Equation¶

To derive the wavefunction of a bound system, we need to solve the quantum “equation of motion” for the electron(s) in the corresponding confining potential: this is the Schrödinger equation. The Schrödinger equation gives the fundamental mathematical description of quantum systems, describing the time-evolution of their wavefunction. The equation for a single non-relativistic particle can in the position representation be written as

where is the reduced Planck constant, is the electron mass, and is the potential, e.g., Coulomb potential of a nucleus in the case of an atom. Mathematically, the Schrödinger equation is linear partial differential equation that assigns a complex number to each point at time , which can be interpreted as the probability amplitude of the electron.

The equation can only be solved analytically for a handful of simple cases, of which the hydrogen atom is an illustrative example. For many such cases, we look for stationary solutions and can thus use the time-independent form the Schrödinger equation, written as

where wavefunctions are the eigenvectors and energies the eigenvalues of the system.

Electrostatic Potentials¶

The electrostatic potential of a specimen determines not only how the electrons of the system are bound, but also how transmitting electrons scatter via the Lorentz force. It therefore connects the properties of the material to the resulting images or diffraction patterns. The electrostatic potential is fundamentally speaking derived from the electron density of the atoms in a specimen, which is described by their quantum mechanical many-body wavefunction. However, this is only rarely analytically solvable, and various approximations may be needed.

In the case of the hydrogen atom, an analytical solution is possible. To describe the confining effect of the proton of the nucleus on the lone valence electron, we need to include the attractive Coulomb potential in the Hamiltonian. Using the time-independent Schrödinger equation, this can be written in spherical coordinates as

where is the elementary charge, is the permittivity of free space, the distance from the nucleus, and θ and φ are respectively the spherical polar and azimuthal angles. The well-known normalized solution can be expressed as

where the quantum numbers ( ) numerate the possible states of the electron, with the Bohr radius , and is a generalized Laguerre polynomial of degree , and is a spherical harmonic function of degree and order .

To calculate the electron density, we need to select a set of quantum numbers ( ); for the ground state, we can choose , . The wavefunction thus simplifies to

whose squared norm gives the (non-relativistic) electron density of hydrogen as

Scattering from a Potential¶

To understand how electrons scatter from a potential, we can consider an electron plane wave incident on an isolated atom. The wave interacts with the electrostatic potential of the nucleus and electrons of the atom, and an outgoing spherical wave is generated. To understand the effect of the atom on the wave, we need to calculated the distribution of scattered intensity, which is not isotropic due to the initial linear momentum of the incident wave.

The scattering problem can be formally treated by finding a solution of the Schrödinger equation (1.4) for the incident electron inside the scattering atom (with electron coordinates )

which we can re-write as

with the substitutions

This can be formally solved with the help of Green’s function (we refer the reader to Fultz & Howe (2013) for detail) to yield a sum of the incident and scattered components

While this formal solution is in principle exact, it is in the form of an implicit integral equation whose solution ψ appears both inside and outside the integral – indeed, we have merely transformed the differential Schrödinger equation into an integral equation without solving anything. To proceed, some approximation is needed.

Born Approximation for Electron Scattering¶

A widely used approximation to solve (1.12) is the first Born approximation, whereby we replace the full ψ within the integral simply by the incident planewave. In effect, this approximation makes the assumption that the incident wave is not diminished and scattered only once by the material, which is valid when scattering is weak.

By further assuming that the detector is far from the scatterer, which allows us to work with outgoing planewaves instead of spherical waves, and by aligning the outgoing wavevector with the direction , as well as assuming that the origin of the coordinate system is near the atom so that , we can write the Green’s function as

By substituting this to (1.12) we get

By further defining , we can write the scattered part of the wave as

which is a function of only the difference between the incident and outgoing wavevectors , describes the change in the direction of the scattered radiation with respect to the incident direction (i.e. momentumn transfer). The factor

is called the atomic form factor (or electron scattering factor Kirkland, 2010 and it describes the angular distribution of scattered intensity. In the first Born approximation it corresponds to the Fourier transform of the scattering potential ().

Atomic Form Factors¶

The atomic form factors thus describe the angular amplitude for scattering of a single electron of by a single atom. While the first Born approximation is inadequate for describing real specimens (as electrons typically scatter multiple times when passing through a crystal), this description is quite useful since it relates the three-dimensional Fourier transform of the atomic potential to the scattering amplitude.

In the general case, we can describe the potential as a sum of a negative term due to the Coulomb attraction of the nucleus with atomic number and a positive term arising from the Coulomb repulsion of the atomic electrons with electron density

By substituting this into (1.16) and defining a new variable , so that and rearranging, we get

The two first integrals are simply Fourier transforms of that each yield , giving the general expression for the electron scattering factor of an atom as

For kinematic scattering (where diffraction intensity ) and within the first Born approximation for electrons (i.e. electron scattering factor is the Fourier transform of the total electrostatic potential) this gives the Mott-Bethe formula for a single atom,

relating electron scattering factors with x-ray scattering factors , where is the electron density. This comparison highlights that unlike x-ray scattering (where the nucleus is too heavy to accelerate in an interaction with a nearly massless photon), electron scattering is sensitive to both nuclear and electron charges, with the latter contribution being relatively enhanced for small electron scattering angles (corresponding to small momentum vectors ). The Mott-Bethe formula is a convenient way to obtain the potential distribution from a charge distribution including the nuclear point charge, effectively by solving Poisson’s equation in reciprocal space.

As an example, we can calculate the x-ray form factor for hydrogen in spherical coordinates (c.f. (1.8), assuming that the incident electron wavevector is parallel to the axis. In this spherically symmetric case, the x-ray form factor reduces to a radial integral

where the exponential term of the Fourier transform has been expanded as a trigonometric integral. We can calculate the integral explicitly as

Using the definition of the Bohr radius (), the electron scattering factor for hydrogen () can then further be written via by the Mott-Bethe formula as

Hydrogen is the only case that is analytically solvable; in general neither the density nor the atomic form factor can be directly written down. Instead, these have been calculated using various approximations to the true multielectron wavefunctions, and tabulated for isolated atoms of all elements as isolated atomic potentials.

Isolated Atomic Potentials¶

Since the Schrödinger equation cannot be solved analytically even for most molecules, let alone solid-state systems, several kinds of approaches have been developed to obtain approximate solutions. These accurate but computationally very expensive techniques have been used to parametrize what are called isolated atomic potentials – or, equivalently in reciprocal space, electron scattering factors – which describe the potential of a specimen as a sum of isolated, non-interacting atom potentials. This approximation is often called the independent atom model.

A potential parametrization is a numerical fit to such first principles calculations of electron atomic form factors that describe the radial dependence of the potential for each element. One of the most widely used parametrizations is the one published in Kirkland (2010), who fitted Dirac-Fock scattering factors with combination of Gaussians and Lorentzians. In 2014, Lobato and Van Dyck improved the quality of the fit further, using hydrogen’s analytical non-relativistic electron scattering factors as basis functions to enable the correct inclusion of all physical constraints Lobato & Van Dyck, 2014.

An example of independent atom model scattering factors and potentials for several elements up to is shown in Figure 1.1.

Density Functional Theory Potentials¶

Since the complicated many-body interactions of multiple electrons mean that wavefunction cannot in general be analytically solved, further approximations are needed. Density functional theory (DFT) is the most prominent one and is widely use for modeling the electronic structure of molecules and solids. In DFT, the combinatorially intractable many-body problem of electrons with spatial coordinates is reduced to a solution for the three spatial coordinates of the electron density that can be variationally reached. This approximation would in principle be exact, but a term that describes electron exchange and correlation is not analytically known and must be approximated.

Although the ground-state electron density for all electrons, including those in the core levels and in the valence, can in principle be solved within the DFT framework, the electron wavefunctions rapidly oscillate near the nuclei, making a numerical description computationally very expensive. To make calculations practical, some partition of the treatment of the cores and the valence is therefore typically needed. Pseudopotential Schwerdtfeger, 2011 and projector-augmented wave (PAW) methods Blöchl, 1994 have in recent years matured to offer excellent computational efficiency. The core electrons are not described explicitly in either method, but in the former are replaced by a smooth pseudo-density, while in the latter, by smooth analytical projector functions in the core region.

Inverting the projector functions allows the exact core electron density to be analytically calculated, making the PAW method arguably ideally suited for efficient and accurate ab initio all-electron electrostatic potentials. The PAW method is accordingly the approach chosen for abTEM, specifically via the grid-based DFT code GPAW (more details on the method can be found in the literature Blöchl, 1994Enkovaara et al., 2010). Notably for our purposes here, GPAW allows the full electrostatic potentials (with smeared nuclear contributions) to be efficiently calculated for molecules and solids and seamlessly used for electron scattering simulations using abTEM.

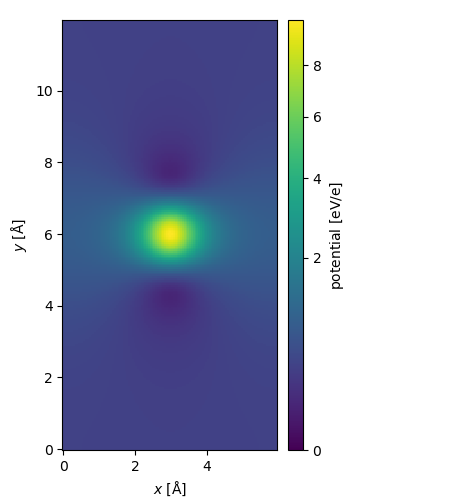

To come back to our hydrogen example, we can analytically calculate its full electrostatic potential by solving the Poisson equation for the charge density of the electron (charge ) combined with the Coulomb potential of the nucleus (). The Poisson equation is

with the solution

This expression is singular at the origin due to the point charge of the nucleus, but that singularity gets smeared out due and numerically discretized in practical calculations (by default, GPAW smears the nuclear potentials with a Gaussian function).

In Figure 1.2, we plot the exact solution of (1.25) against the Kirkland IAM parameterization as well as a DFT calculation using the GPAW code. While all models agree perfectly near the nucleus (the discontinuous appearance of the line is due to a finite computational grid with a spacing of 0.01 Å), where the potential is the strongest, small differences emerge further away. In the case of the DFT model, the simulation box is finite in size, and thus the continuity requirement of the wavefunction and corresponding density slightly affect the long-range part of the calculated potential. The choice of exchange-correlation functional may also slightly influence the results.

Although IAM potentials are useful for many purposes, they do neglect chemical bonding, which may be measurable and of interest. To illustrate this difference, an interactive comparison of the IAM and DFT scattering potentials of the H2 molecule at different distances between the H atoms is shown below.

- Fultz, B., & Howe, J. (2013). Transmission Electron Microscopy and Diffractometry of Materials. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-642-29761-8

- Kirkland, E. J. (2010). Advanced Computing in Electron Microscopy. Springer US.

- Lobato, I., & Van Dyck, D. (2014). An accurate parameterization for scattering factors, electron densities and electrostatic potentials for neutral atoms that obey all physical constraints. Acta Crystallographica Section A, 70(6), 636–649. 10.1107/S205327331401643X

- Schwerdtfeger, P. (2011). The Pseudopotential Approximation in Electronic Structure Theory. ChemPhysChem, 12(17), 3143–3155. 10.1002/cphc.201100387

- Blöchl, P. E. (1994). Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B, 50(24), 17953. 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953

- Enkovaara, J., Rostgaard, C., Mortensen, J. J., Chen, J., Dulak, M., Ferrighi, L., Gavnholt, J., Glinsvad, C., Haikola, V., Hansen, H. A., Kristoffersen, H. H., Kuisma, M., Larsen, A. H., Lehtovaara, L., Ljungberg, M., Lopez-Acevedo, O., Moses, P. G., Ojanen, J., Olsen, T., … Jacobsen, K. W. (2010). Electronic structure calculations with GPAW: a real-space implementation of the projector augmented-wave method. J. Phys. Condens. Matter, 22(25), 253202. 10.1088/0953-8984/22/25/253202